On the night of Wednesday, June 17, nine African-Americans were gunned down during choir practice at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, SC.

On Thursday June 18, the interns of Cold Case Justice Initiative arrived at work and sat looking at one another. What was there to say? Some of us were confused, some of us were angry. We were all depressed, forlorn by the awful resonance of the past in the present. Everything that we have been working on this summer… all of the cases we have been investigating… it’s horrible. And yet, after the massacre of nine innocents last night, we were shown that the fight is not over. Not by a long shot. By no means do we live in a color-blind world. By no stretch of the imagination do we live in a post-racial society. If ever there was a nightmarish moment in America, it could not have been worse than Wednesday night. We did this to ourselves.

That morning, we talked about it some, but what had happened was still a shock. We tried to go on with business as usual. But it was impossible. It was impossible to evade the terrible implications: the persistence of hate, the magnitude of violence, the meaning of death for nothing. That is, nothing more than the arbitrary facts of skin color and identity.

The events of the week were altered by the fact of the shooting. We tried to go about our business, but everything was filtered by the shooting. It changed the meaning of what we were doing. While we thought we were looking back behind ourselves in an exercise of abstraction, our perspectives became as if autoscopic. We saw ourselves from outside of ourselves, rocked into our own moment, as the past exploded into the present, shot from the barrel of an assailant’s gun.

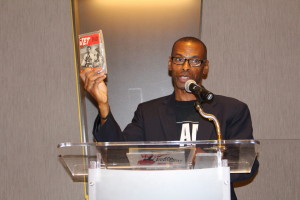

On the preceding Friday, June 12, we had met with Tyrone Brooks in the Atlanta offices of the CCJI. Mr. Brooks is a former Georgia State Legislator and Field Director of Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Dressed in a tan button up and brown pants, Mr. Brooks appeared the wizened civil rights leader he is. He began by explaining to us that he has transitioned out of legislative politics to fully dedicate his time to advocate for the victims of the Moore’s Ford Massacre, a lynching of two young black couples that occurred in Munroe, GA in 1946. The tragic event marks the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, as it led President Truman to form the first ever Civil Rights Committee focused on the issue of lynching black people in the United States. Despite a year long FBI investigation into the Moore’s Ford Massacre, there were few indictments related to the event and no convictions ever occurred. In effect, the FBI investigation of the Moore’s Ford Massacre has, up until this point, entirely failed to achieve justice.

Mr. Brooks’ civil rights career began early, when as a 15-year-old student he was arrested for protesting in Covington, GA. A couple years later, in 1967, Tyrone Brooks came to Atlanta with the SCLC. Rev. Hosea Williams, Dr. King’s field general, brought him. Hosea Williams was a populist hero, conducting voter registration every summer, donning overalls at times, sporting suits at others. At 21, Tyrone Brooks found himself in front of Dr. King himself. Dr. King said, “I don’t do hiring. Take him to Abernathy. Put him on the pay roll.”

During his time with the SCLC, Mr. Brooks told us, he was in jail for 45 days as the field director of the organization. “Jailing for freedom is an honor,” he said, quoting Nelson Mandela.

Reflecting on 1968’s Poor People’s Campaign, Mr. Brooks told stories about the Mule Train to DC through the South starting in Marx, MS, then the poorest county in the U.S. “[On the train were] heroes and sheroes,” he explained. Initially, the Mule Train wasn’t allowed to pass through Georgia, and the riders spent time in jail for trying to do so. Once they were released and allowed to cross the state, they helped set up a tent city on the Mall in DC. They marched all over the Mall and went to jail there. Mr. Brooks thought it was remarkable that they were sentenced to time in jail by a black judge for marching without permit. It goes to show you that institutionalized racism can be personally mediated by anyone, no matter what the color of their skin.

Tyrone Brook was 22 years old, serving on the field staff of the SCLC when Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed in Memphis. Mr. Brooks was in Munroe “when the bullet hit him[MLK],” and once he heard the news, Mr. Brooks drove all night to join the SCLC leadership in Memphis. It was a chaotic time for the organization.

Reflecting on the changes between today and yesterday, in light of the cases being worked by the CCJI, Mr. Brooks quoted Joseph Lowry, the storied civil rights leader. “Everything has changed, and nothing has changed.” He grew quiet for a moment, looking down as if contemplating a vision of the past. Mr. Brooks looked up and concluded, “The movement is forever, the struggle continues.” We didn’t realize it then, but his words would seem prophetic in light of the coming week’s events.

On Monday, June 15, blithely unaware of the attack that would transpire in the coming days, Alphonse and I headed downtown to the county court house. All the property records for Fulton County are located there. We wanted to find out who owned the property where the victim from our case was killed. After entering through the metal detectors and security guards stationed at the front door, we descended on the elevator to the bottom floor. An air of dust and decay reached our nostrils as we stepped through the double doors. We looked at each other and rolled our eyes. We remembered last week when the reverend had told us we were archaeologists of justice. Today, it really felt like we were archaeologists. Amongst the batty property lawyers roosted amongst the dusty tomes, we conducted our search of property records. Recent records are digitized, so we started on a computer, found the deed for our address, and worked backwards from there. At noon, we walked down the street to get out of the hot sun and eat lunch in the cool, cavernous cafeteria in the Secretary’s state building. They have a Chick-fil-A, so we gorged on fried chicken sandwiches and sweet tea. After lunch amongst the state employees, we returned to the tomes, and, after a couple hours, we tracked down the deed for our property the year when our victim was killed. We drove away victoriously. Later that afternoon, Alphonse also found the name of the officer who killed the victim in our case through an open records request. Monday was a productive day for our investigation.

On Tuesday, we filed records documenting all the work we’ve done so far, so that others can follow the trail when we finish our term with the project at the end of the summer. We still didn’t know what was coming.

On Wednesday, June 17, while the other students were away at the library, Professor McDonald told stories about interning for Robert Kennedy before law school, her transformation “from an armchair liberal to being arrested for civil rights protests,” and her time at Yale Law School. Alphonse then explained the experience of being the only black student in his section at Syracuse Law, where a fellow student, a white farm boy could say something, genuinely meant to be supportive but without understanding the racial significance of what he had said.

However, explanation is not justification. The violence of accidental racism in private education is common today, when the market value of diversity brings a small number of black students into contact with a large group of uncultured, insensitive white students. This is not an isolated event. Racism, accidental or otherwise, is culturally prevalent all across the country at higher-level educational institutions, especially those that are historically white.

Accidental racism shares its source with its more sinister sibling, intentional racism: the mother of America, white supremacy. The problem with our educational institutions today is that they pander to affirmative action while still allowing white supremacy to thrive ideologically. As writer Ta-Nehisi Coates of The Atlantic has suggested in “The Case for Reparations,” it is inadequate that modern reparations should find primary expression in higher education, because the legacy of black slavery in America is so far reaching, covering every facet and field of social life, extending far beyond the educational infrastructure. In essence, its not the white-farm-boy-turned-law-student’s fault that he mistakenly said something racist to Alphonse. The fault belongs to all of us, for allowing white supremacist views to continue saturating our culture, both in and outside the classroom. Free speech is one thing. Moral imperative is another. The fact that, as a community, we have allowed white supremacy to continue infecting our institutions and our personal lives led to the events of that night, when the nine innocents were shot to death in Charleston.

Thursday afternoon, we met with Elizabeth Wilson, mayor of Decatur from 1993-1999, in our offices at Oakhurst Presbyterian. The day was hot, so we had the A/C on blast. Currently, Mayor Wilson is leading a courageous battle against the forces of gentrification in Decatur, what she called “a racist program.” Mayor Wilson is fighting specifically in the neighborhood surrounding the church where we work. When Alphonse introduced himself as living off Candler Road, she remarked mirthfully, “Oh, you are real local.”

Professor McDonald started off by introducing Mayor Wilson to our cases. “The families don’t know about our work,” she said, “or we don’t think they know. We have turned over 90 cases to the Georgia DOJ, but there’s been no movement… [Often, we see that] one cop was the killer, another was the detective, [and the whole thing was] hushed up; then [they] reversed roles on next case.” Sometimes, it feels like everybody was “in” on the racist killing of black men in Atlanta.

Mayor Wilson nodded in understanding. Then she told her story: “When I moved to Decatur in 1949, [I] moved from Greensboro, GA, 80 mile east of Atlanta… [In 1949,] the Klan, the Grand Wizard was here, residing in Stone Mountain. [They held] meetings in downtown Decatur. I lived in public housing downtown. [The Klan] paraded in the square. Some of us had become active with Dr. King and the student movement. So we went down to the square to see. Everything you hear is true. Costumes, racial hatred. Seems like that’s what they enjoyed…”

Mayor Wilson went on to explain her experience living at that time: “[I] could never go anywhere by myself. White men rape black women. [I was] scared my entire life growing up.”

Then, she elaborated on Klan operations. “The Klan headquarters was in Stone Mountain,” she told us. “At the foot of the Mountain was a black community. They [the Klan] tried to terrorize them [the blacks]… Later, the first black mayor [of Stone Mountain] bought the house where the Grand Wizard [had] lived.” We were puzzled by the irony. Mayor Wilson threw us a small smile in conciliation. “Venable ??was the Imperial Wizard,” she revealed. “[He had] one of the houses on the corner outside the courthouse. [He] had a black man sitting outside his office. [Venable would say,] ‘One of my best friends.’” It’s unbelievable hearing the manipulative ends the Klan went to further their racist pogrom.

Notably, Mayor Wilson explained to us that black officers could not arrest whites in Atlanta, but they could in Decatur.[1] Mayor Wilson reflected, “It always felt like they [the black police officers] were very nervous.”

She went on, “The area [was] in transition from white to black. We were trying to get to know each other. White flight began, and we were just trying to find a place to live… School populations rapidly changed. [The] Principal left. Neighborhoods gone from being all white to all black… Up until 1967, [there were] two black high schools.” After white flight occurred, the schools were all black.

On the racial profiling that made the Decatur police infamous and that still goes on today, Mayor Wilson said, “[There was] racial profiling. [There was] harassment. [The white police would say,] ‘Boy this,’ ‘Boy that.’ One lady had a seizure, [they assumed] she was drunk, [and] threw her in jail. But she was actually very ill. [She] didn’t [even] drink, and she died.” She told us a story we had heard before, about Dr. King being arrested in Decatur for riding in a car with a white woman on the Emory campus, on his way to the hospital with a broken arm. Ironically, both King’s wife and the woman’s husband had been in the car at the time. The story indicates the extent to which race determined policing outcomes, no matter the circumstance.

Mayor Wilson then circled back to the issue of public schooling in Decatur in the 1960s within the context of a rapidly changing racial dynamic. By 1962, Wilson had become highly involved in the community. She was active in the Wheat Street and Ebenezer Baptist Church communities, two historically engaged black communities located off Auburn Avenue.[2] Through community protest, Decatur maintained the schools’ PTA despite the consistent opposition of principals and administrators.

Mayor Wilson was insistent that widespread prejudice and active discrimination of blacks defined the time. When employers found out that men had joined the NAACP, they were fired.

There were some good times, like when baseball legend Jackie Robinson came to Decatur in 1961 to help register people to vote and to register people in the NAACP. But the good was tempered with the bad, as Mayor Wilson remembered that people were generally afraid to come through Decatur in the 1960s, when there was no highway 285 running East-West to travel across town.

Mayor Wilson remembered that, in Atlanta during the 1960s, the segregation was extreme, as symbolized by the white and black neighborhoods separated by a wall in between at Peyton Road in Southwest Atlanta, something resembling East and West Berlin following World War II. She remembered parks for blacks only. “[We] could not go to Piedmont Park,” she said.

When we asked Mayor Wilson about the connection between the police and the Klan in the 1960s, she paused to think for a moment. “Some were members, and if not members, they acted like it. The whole department, they all looked the same and behaved the same. From the chief to the rookies.”

She paused again and looked down, thinking. When she raised her head again, a look of profound intensity burned in her eyes. “We were very aware of everything going on, especially police harassment, police brutality.” She paused. It looked like she would continue, but she didn’t. She looked off, as if something had carried her away.

Professor McDonald took the chance to tie it all back to the CCJI’s mission. “There’re connections between what’s happening now at the AME church and what happened then. We need to cleanse those wounds… Students then [were] pushing for name tags on cops, [and] students now [are] pushing for cameras.”

Mayor Wilson took up this theme of the past in the present. “I see some change in attitudes…” She grew silent. Ultimately, she concluded, “The fight is still going, but its not near as bad as it was.”

Though she might be right, the day after the massacre at the AME church in Charleston, things felt unspeakably bad. The significance of the past in the present has defined our summer. Then and now. Many people would have us believe, then, not now. But after the mass shooting, now feels exactly like then. Without justice for then, how can we expect to prevent tragedy now?

Charleston made us realize the importance of what we are doing, the importance of making a record and impressing upon the larger community the nature of what has happened. Maybe, by making a record, by educating people about the tragedies that have occurred, by advocating for the families of the victims, we can prevent more from occurring in the future. Maybe… maybe there is nothing that can be done. But we refuse to accept defeat. Justice delayed will not be justice denied. We will fight to the end. To alleviate the injustices of the past, to address the wrongs of the present. The memory of the nine at the AME church in Charleston demands nothing less.

[1] This seemed interesting in light of what Civil Rights attorney Davis had told us the week before, that neither Jewish nor Black attorneys were permitted to join the Decatur bar until 1985. Though ever present, it seems like the racism infecting the institutions in Decatur was complex, operating in different ways in different sectors of the community at different times.

[2] Both Wheat Street Baptist Church and the Ebenezer Baptist Church comprise politically active communities today, and the CCJI is involved with both.