CCJI Summer Orientation Program, May 30, 2015

The Cold Case Justice Initiative (CCJI) works in response to William Faulkner’s principle. The evils of the past have not yet been resolved by the arm of justice, so the past is not only with us and a part of us: that evil still lives in our midst. Accordingly, on Saturday, May 30, 2015, the CCJI hosted a day of panels at the Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia. While thirsty patrons of the Coca-Cola museum guzzled down soda on the lawn above, the CCJI diligently pursued long-overdue justice for the community, just as it has been doing for the past eight years. Entitled Past & Present Families United: Justice & Accountability for Racist Killings, the event operated as an orientation program for CCJI’s summer interns. Presenting the voices of family members of the victims of racially-motivated violence and their continuing quest for justice, as well as members of the media who investigate these cases and inform the public about the continuing need for awareness, and advocates and activists who work with family members and communities to obtain justice, the event contemplated the meaning and legacy of the unsolved civil rights crimes cases. The day also saw a strategic discussion for concrete ideas for the pursuit of justice and accountability and ways in which CCJI law student interns can advance these causes in collaboration with families, communities, and social justice organizations and governmental organizations.

The day was marked by pathos, power, and tears. We heard from families still fighting for justice decades after suffering their loss. Joyce Dorsey and Jessica Malcom, representing the Moore’s Ford Bridge Massacre families, and Janice Cameron and Nedra Walker, representing the families of the Five Atlanta Fishermen Killed in Pensacola, Florida, represented the awful trials and travails of pursuing justice decades after their loved ones died. Shelton Chappell, the youngest son of Johnnie Mae Chappell, spoke of the sharp pain he and his family still feel over his mother’s death fifty-one years ago. Denise Jackson Ford and Wharlest Jackson, Jr. conveyed the love that the Natchez, Mississippi community still feels for their father, Wharlest Jackson, Sr., and their staunch refusal to accept the warped logic in the FBI’s closure of their father’s case. And showing the parallel suffering wrought upon the community today, Martinez Sutton, brother of Chicago’s Rekia Boyd, wove the narrative of insensitivity and legal incompetence that surrounds his sister’s recent death at the hands of a Chicago police officer.

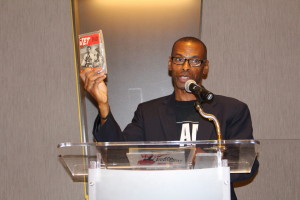

Allies of the families of the dead, representing the political structure and the media, conveyed the urgency of making the struggle for justice imperative upon the community. Tyrone Brooks, a former Georgia State Representative, depicted his ongoing struggle in and outside of the legislature to obtain justice for these families. Pulitzer Prize–nominee Stanley Nelson of the Concordia Sentinel in Ferriday, Louisiana explained the difficulty of providing news coverage for unsolved civil rights cases in local newspapers. Pulitzer prize–winning journalist Hank Klibanoff, director of the GA Civil Rights Cases project at Emory University, explained the challenges in teaching today’s students about outstanding civil rights crimes. Angela Robinson, president of A.R.C. Media, LLC, touched on the importance of holding television news stations accountable for their framing of civil rights stories. And, Derrick Boazman, radio host of Atlanta’s “Too Much Truth,” pointed to the power of radio in telling the stories of unsolved civil rights crimes.

In looking towards the present and future, allies of the CCJI engaged in a round table discussion of strategic decision making in the realm of unsolved civil rights cases. Understanding the larger social context surrounding these cases is paramount to addressing them properly. Accordingly, Joe Beasley of Rainbow Push; Deborah Watts of the Emmett Till Family Legacy Foundation; C.B. King, the famed civil rights attorney; Rev. Dr. Francys Johnson, president of Georgia’s NAACP; Mawuli Davis, a prominent civil rights attorney; and Aurielle Marie, of Atlanta’s It’s Bigger Than You, worked together to identify particular problems in the community and appropriate means for addressing those problems.

Finally, professors Janis McDonald and Paula Johnson of Syracuse College of Law, co-directors of the CCJI, presented the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act of 2007 and its failings. While exhorting the FBI and Department of Justice “to expeditiously investigate unsolved civil rights murders, due to the amount of time that has passed since the murders and the age of the potential witnesses” and “provide all the resources necessary to ensure timely and thorough investigations in the cases involved,” the Emmett Till Act has failed to initiate adequate action by either branch. The directors indicated the intention of the CCJI to advocate for amendment and extension of the Emmett Till Act so that justice may be attained.

Justice delayed is only justice denied if we accept failure. Saturday’s panels reaffirmed our refusal to accept the failure of justice. Though the U.S. has no institution devoted to human rights, investigation of the genocide committed here against African-Americans is ongoing. As long as the community calls for it, the CCJI is committed to continue the fight for justice by any means necessary.

Brent Lightfoot

CCJI Summer Intern

Emory University School of Law